Every now and then at Strathblane Heritage, a true gem falls into our laps that lights up a facet of local history at risk of being lost forever.

While the Carbeth Hutters are rightly famous and celebrated, few today remember a parallel but quite separate movement that enabled scores of working class families to escape the pollution and overcrowding of Glasgow and run free in the beautiful countryside around Strathblane.

If it had survived, the Fellowship Camping Association at Carbeth would be celebrating its centenary in 2026. But although its members struck camp for the final time in 1966, its four decades are celebrated in the memories of two of its veterans and a truly remarkable photograph album produced by a relative of one of them.

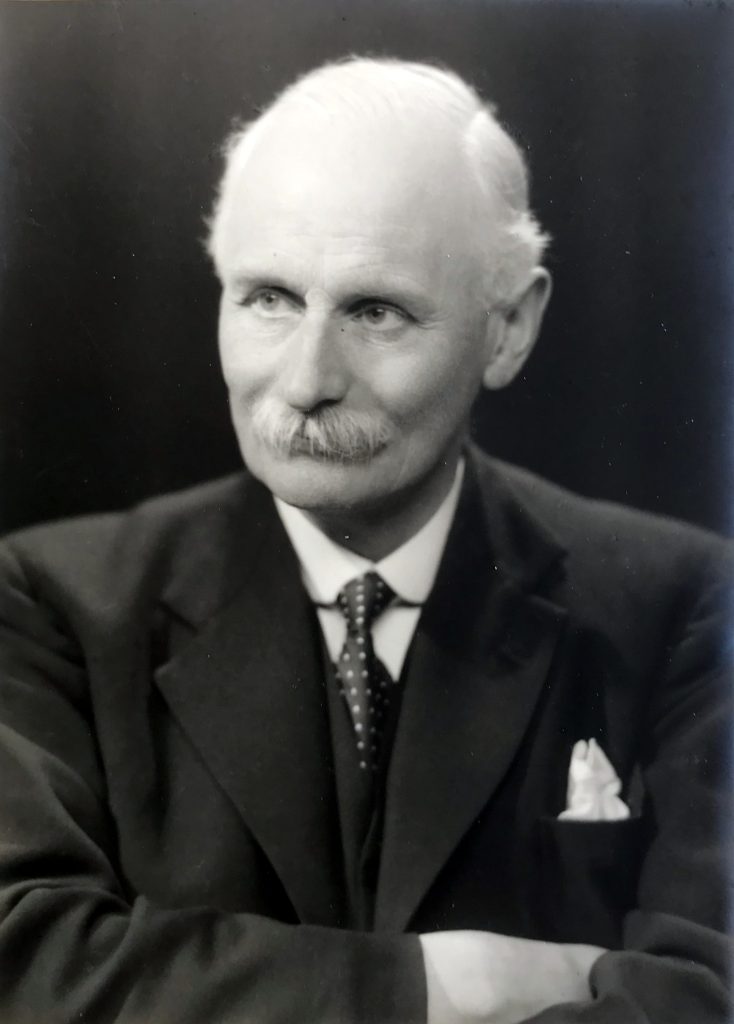

The association was formed in 1926 in a field off the Cuilt Road at Carbeth, following an agreement with open-minded local landowner Allan Barns-Graham, grandfather of the present proprietor.Today Ellen Park is a widow living in Strathblane but she was born Ellen Summers in 1937 in a second-floor tenement in the East End of Glasgow. “My grandfather, Jim Fulton, was a founder member. He’d been part of the Clarion Cycling movement and the camping association at Carbeth grew out of that.” [The Clarion Cycling Club was formed in the 1890s by a group who wanted to combine their love of cycling with their left-leaning politics and needed cheap transport to enjoy the countryside and reach a wider audience.]

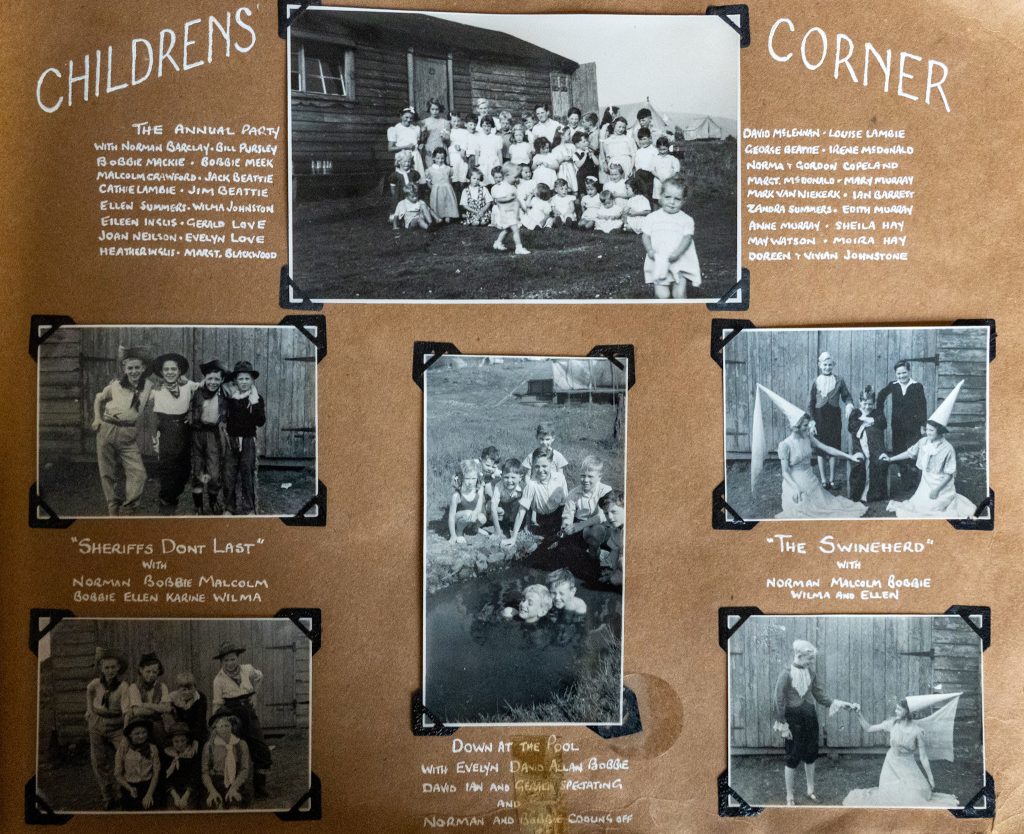

Ellen’s Uncle, also named Jim Fulton, has immortalised the history of the Carbeth association in a delightful, annotated photograph album that catches its blithe spirit.

Ellen said: “The rules were very strict. The camp opened from April until early October. You had to buy your own tent from Blacks of Greenock and the wood that was laid on foundations to make a floor. You’d cover that with linoleum and old carpet. The tents were held up by poles on the inside and guy ropes outside. Light came from Tilly or Primus lamps. There were two sizes of tent. In the bigger ones some put a curtain across to create a room for the children to sleep.”

Lifelong friendships sprang up between camping families. It’s where Ellen met her great friend Karine Davison (nee Graham). Karine lived in the centre of Glasgow before moving to Knightswood. She says: “There was a big interest in being democratic and giving people access to the countryside.” Families, who could not otherwise have afforded holidays, scraped the money together to buy a tent: “I found out that after buying their tent in 1948, my parents had only 7s6d left in the bank.”

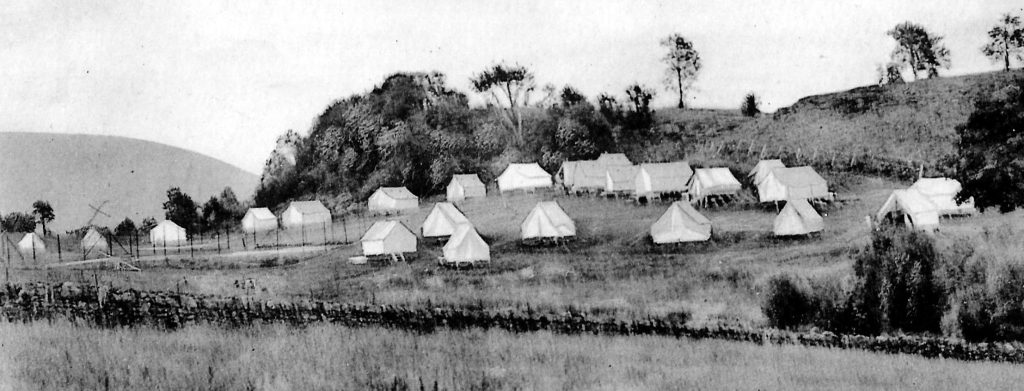

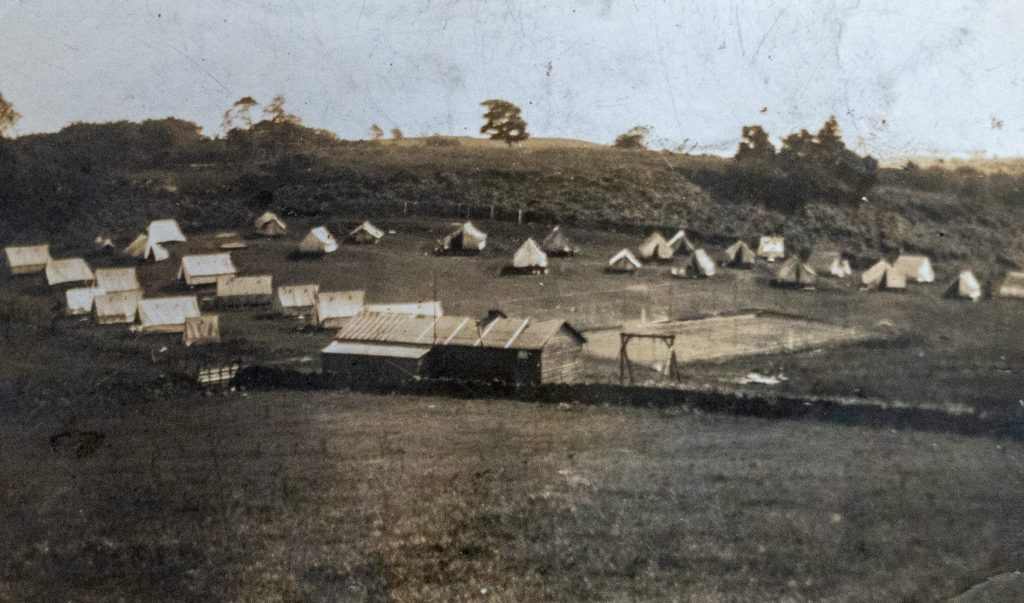

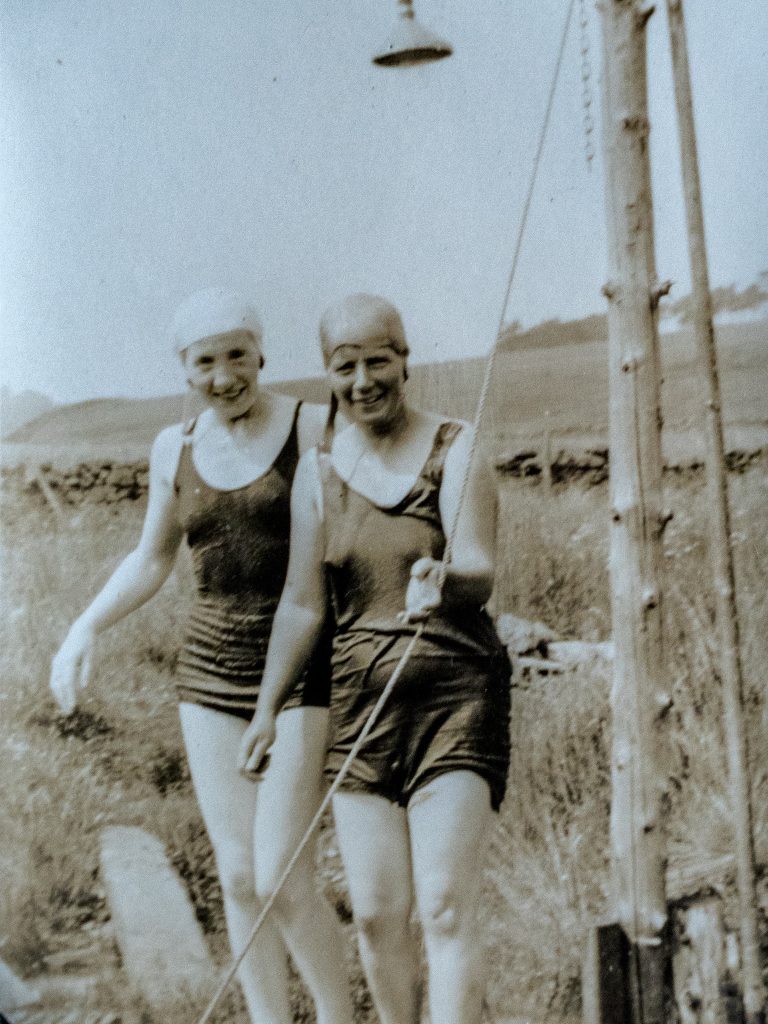

By the end of the 1920s, the campers not only had their own tennis court but also a hut large enough for social events in summer and the storage in winter. At first water had to be collected from a nearby burn in buckets but later a well was dug. Curiously, a trout was reputedly kept in the well to eat the insects. Nobody seemed concerned about fish poo! Here are some pictures from the early days (around 1930).

How did the campers get to Carbeth?

Karine said: “A bus would bring us to the Cuilt Road and all the mothers and children would troop down from there on a Friday evening.”

Ellen said : “There were so many people that the bus company had to put on an extra bus, a double decker.” Campers thought nothing of taking two trams and a bus to reach Carbeth, as Ellen did.

Karine said: “We’d walk down with our mothers to the grocers in Station Road. We used to get a liquorice dab if we were good.” [Latterly, this was Telfers shop, on Station Road, opposite Blane Avenue.]

Basics could be had from the Wee Shop, run by the Inglis family, who slept in the back of the shop. It was at the junction with the Stockiemuir Road. [There is a modern house there now.]

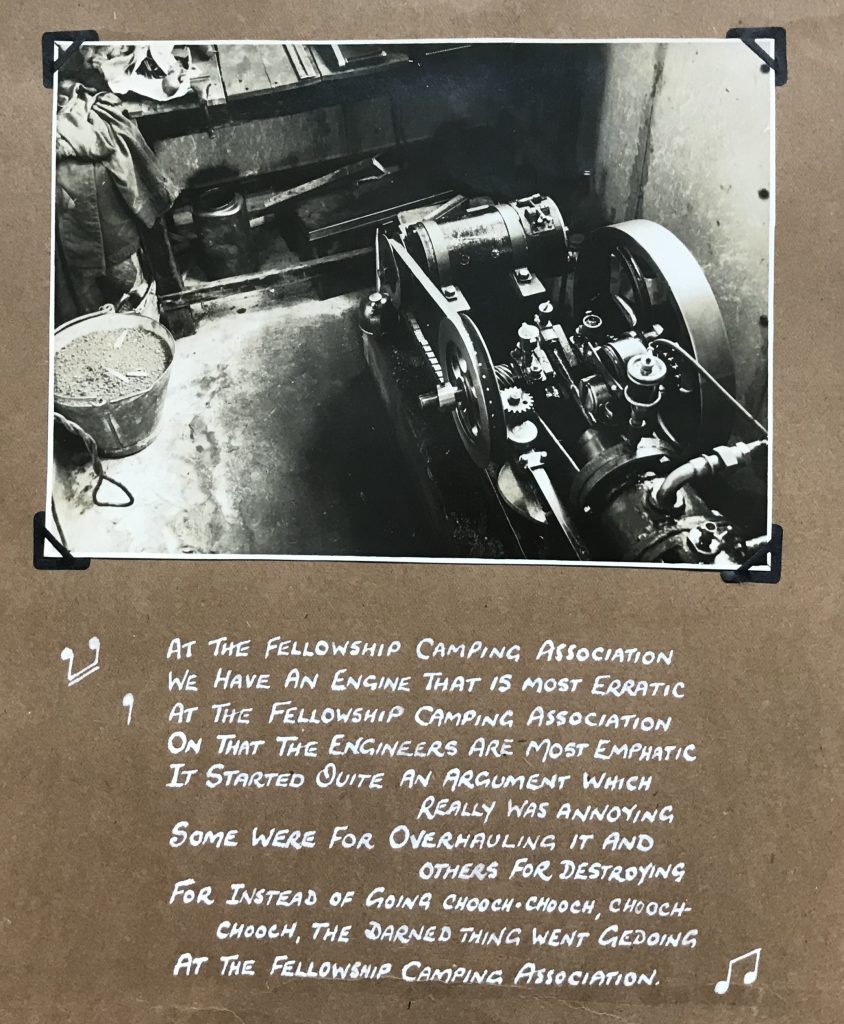

Ellen says: “Everyone turned up for the grand opening. We would take our mattresses down to Cuilt Farm to get filled with chaff and straw. They were horribly itchy! We would stay out at Carbeth for the whole of the school holidays. At the end of the season the wooden floors were stored beside the big hut the men built where we had dances and parties. There was a generator that sometimes went on the blink. On Saturday nights everyone gathered in the hall. Most Saturdays families took their own tea with them. You’d take down your own cup and biscuit but on the May weekend, the Glasgow Fair Fortnight and the September weekend the women would all bake and we had a feast. On those nights you could dance until 1am.

“There was a great social life. The women would gather outside their tents to talk and knit.

The men had a work party on Sundays. Everyone pitched in, with men who knew about carpentry and building showing the others what to do.”

Karine said: “Several generations of huts were built, culminating around 1950 with a hall about 60ft by 30 ft complete with stage and kitchenette. On Saturdays there were sing songs and dances in the hut. We did the Gay Gordons and the Valeta and there was a band just made up of whoever could play something. My Dad played the piano accordion. There was a piano, a banjo and a guitar. One man played a tea chest with a pole and string! (It was a sort of primitive double bass.) Some of the men would dance in wellies.”

The big hut boasted a generator, which was a boon when it worked. However, it was rather temperamental, as demonstrated by this ditty.

What about toilets? Karine recalls: “They were pretty basic. Just a wooden bench with a hole in it and a dustbin lid to cover it. There was a rota for cleaning them. Two of us girls got 3s 6d between us for volunteering to do that! Emptying was the men’s job. There was an incinerator for rubbish and slops.”

There was a good relationship between the campers and landowner Allan Barns-Graham, who used to say: “I DO like my campers.” There was surprisingly little contact between the campers, who mostly came from Glasgow, and the hutters, who were predominantly from the Clydebank area, according to Ellen and Karine, though both groups later used the swimming pond, opened by the Barns-Grahams in the 1930s. “We used to march up the road with our towels under our arms,” remembers Karine.

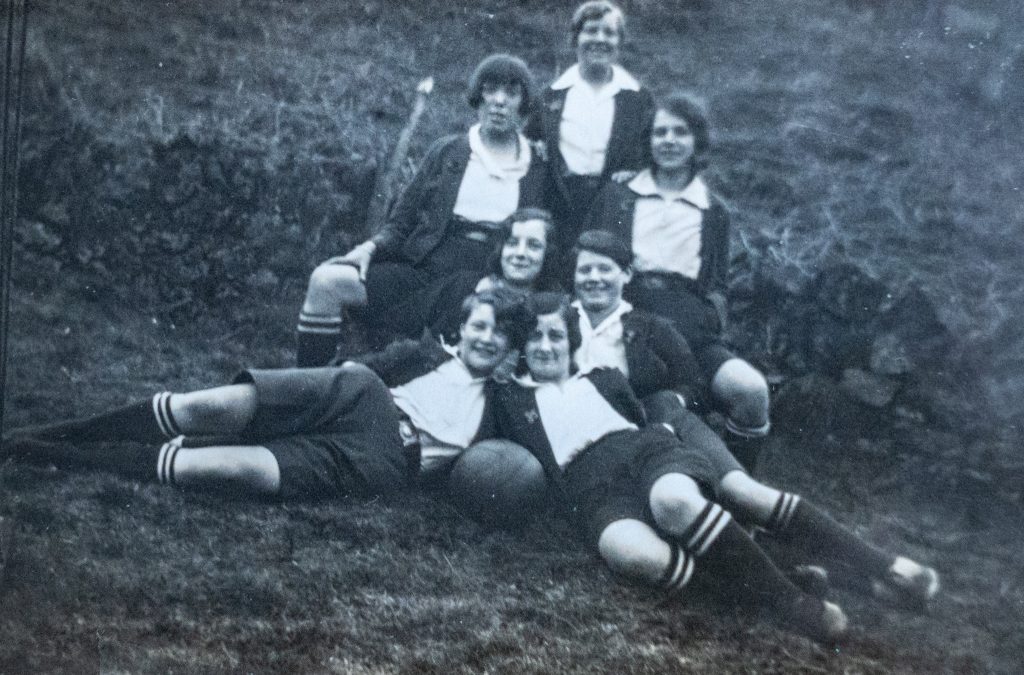

From the start football was played at Carbeth, including women’s football.

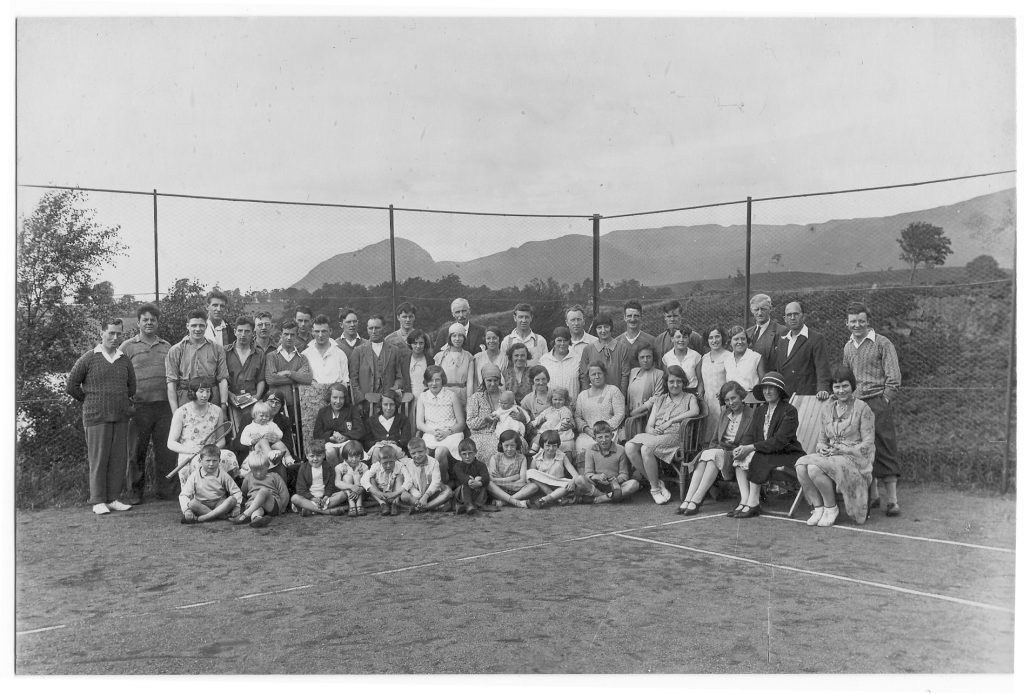

In the early days the campers were reliant on invitations from the Barns-Graham family if they wanted a game of tennis.

However, by the mid-1930s, the campers at Carbeth had built themselves a hard court and tennis remained a favourite pastime throughout the history of the Fellowship Camping Association.

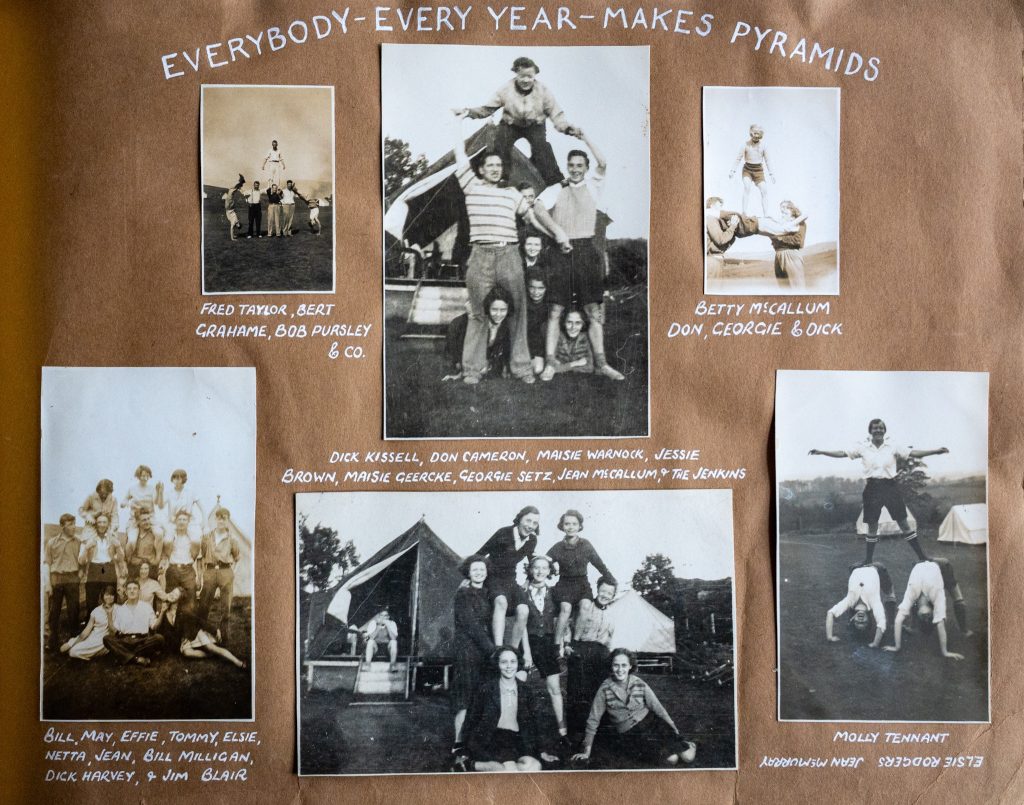

And, as observed here: “Everybody, every year, makes pyramids.”

One bonus of the meticulous way Jim Fulton annotated his album is that it shows over time new generations of the same families returning to Carbeth with their children. Some of them would end up living in Strathblane.

Nobody needed an excuse to dress up! Here’s an example from 1949:

During the summer of 1938 the Carbeth campers hosted a visit by child refugees from the Spanish civil war:

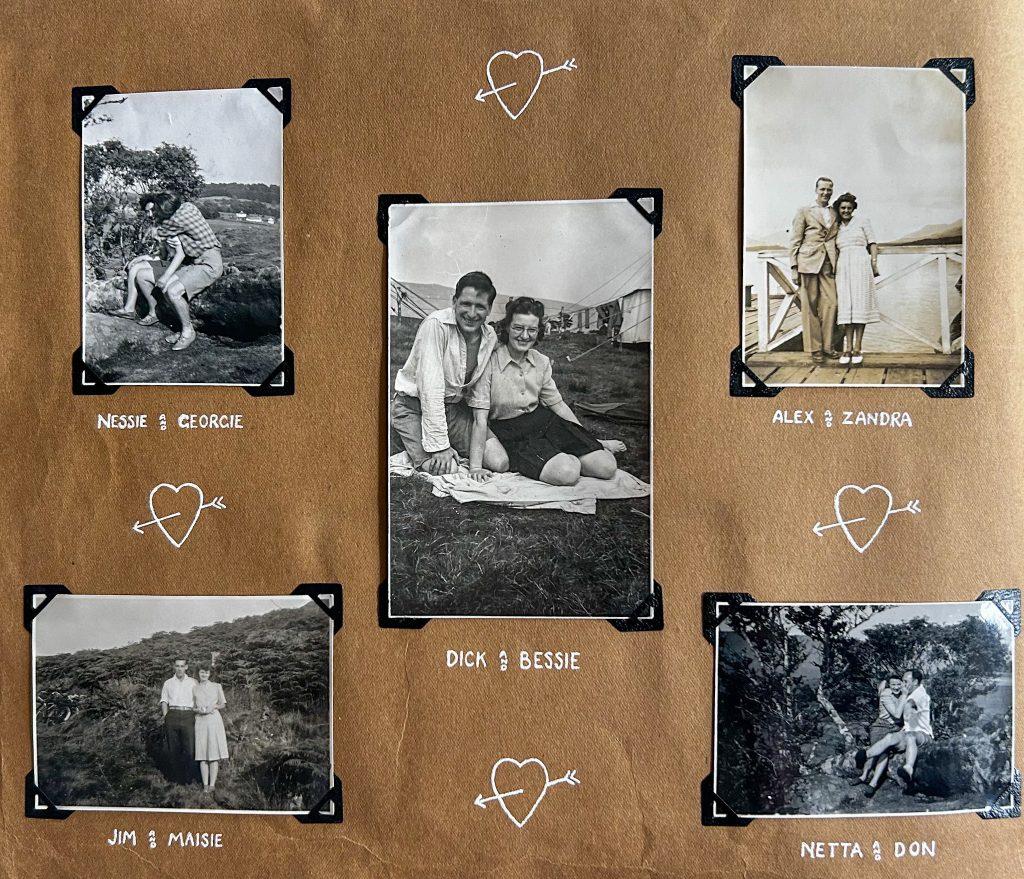

Predictably, perhaps, many members of the Fellowship Camping Association met their future partners at Carbeth:

They included Ellen Summers, as she was then. A third generation Fellowship Association camper, she was a teenager climbing a tree at Carbeth when she first spotted 21-year-old Joe Park, who had just been demobbed from the RAF: “I didn’t like him at first but gradually things changed!”

Her friend Karine met her mate Ian Davison when he was evacuated to Carbeth because of a threatened explosion on board a ship at the docks by Yorkhill. After their marriage, they got the loan of a tent for two years.

From the start, by agreement with the Barns-Grahams, the camp was packed up each year at the beginning of October and the tent bases stacked away until the following spring.

But each winter association members and their children would put on their best clobber and hold a big dance in the MacLellan Galleries in Sauchiehall St.

After the Second World War, several families emigrated though they always came back to Carbeth when they were on home visits. By the 1960s, however, things were changing. The weather took a turn for the worse and the tents weren’t lasting so long as they used to. The Association asked Patrick Barns-Graham if they would replace the tents with bus bodies but he declined. As Karine says: “By now people were using cars to get to the camp and that created problems. And television kept people at home.”

Perhaps, also the rise of the package holiday market meant people’s expectations of what constituted a good summer holiday changed. A string of wet summers didn’t help and in 1966 the Fellowship Camping Association dismantled their tents for the final flitting.

Ellen Park and Karine Davidson still meet regularly to mull over old times.

Many thanks to Ellen Park and Karine Davison as well as photographer Chris Bell, who photographed Karine and Ellen and rephotographed a selection of pictures from Jim Fulton’s album.

Anne Balfour June 2025